Greenwashed and Exposed

The Failure to Protect Communities from PFAS

For decades, we’ve been told that using compost is one of the most sustainable choices we can make for our gardens. Municipalities, state agencies, and industry lobbyists have championed it as a “green” solution, recycling waste into soil nutrients. But as someone who has been deeply engaged in environmental health and policy, I’ve seen how organizations like the Northeast Biosolids and Residuals Association (NEBRA) and the Municipal Association have pushed hard to downplay very real risks.

The science is clear: compost made from sewage sludge, is not benign.

A Loophole in Plain Sight

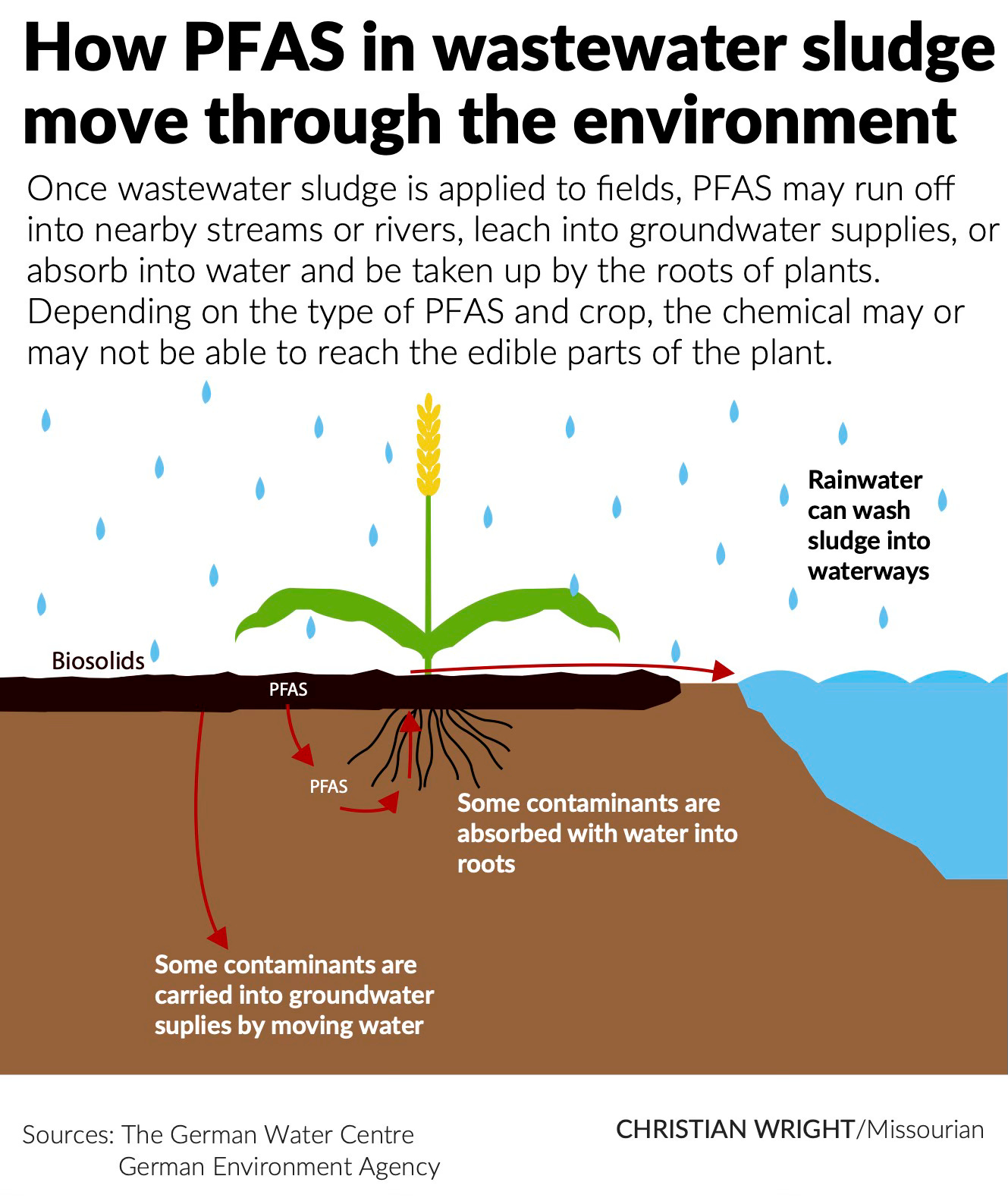

In 2011, the USDA banned sewage sludge in certified organic farming. But outside of the organic label, rules remain far looser. Sludge-based compost can still be sold if it meets basic standards for heavy metals and pathogen treatment. What’s not regulated? Persistent, toxic chemicals like “PFAS” (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances or “forever chemicals”).

This regulatory gap means consumers buying “sustainable compost” have little idea that it may contain PFAS at levels that are invisible to current oversight. The EPA itself now admits that sewage sludge frequently carries PFAS, chemicals that treatment plants cannot effectively remove (AP News).

The Merrimack, NH Example

Merrimack, New Hampshire, is a cautionary tale. Since the late 1970s, its wastewater treatment facility has composted sewage sludge, upgrading to a more advanced in-vessel system in 1994. From a waste management perspective, the program looked like a success: thousands of tons of sludge diverted, compost produced, and sold into the community.

But PFAS doesn’t break down in composting. Instead, it accumulates—seeping into soils, water, and food chains. In 2018, testing of Merrimack biosolids found PFOA at 8 to 15 parts per billion (ppb) and PFOS at 8 to 11 ppb. Since 1986, air emissions from Saint-Gobain’s Merrimack facility have been a major source of PFAS drinking water and groundwater pollution. Now, evidence shows the problem runs deeper: wastewater discharges and compost distributed to residents have quietly contaminated local gardens, long before anyone realized their soil and food supply were being exposed.

By 2019, under local pressure, Saint-Gobain installed a pretreatment system targeting non-detect PFAS discharges. Yet, even as towns like Merrimack demanded stricter controls, Saint-Gobain argued it wasn’t legally obligated to meet standards that didn’t yet exist. Southern New Hampshire residents were caught between regulatory inertia and corporate denial.

Beyond Compliance: The Health Toll

Merrimack residents have paid the price. Decades of exposure have been linked to elevated cancer rates compared with national averages and neighboring communities (PubMed). Scientific evidence continues to mount: PFAS exposure is associated with cancers, endocrine disruption, immune suppression, and developmental harms (ScienceDirect).

Yet compost made from sewage sludge can still be marketed as safe, because PFAS isn’t part of federal regulatory checklists, which is a source of the disconnect: meeting current standards does not mean protecting public health.

The Larger Pattern

Merrimack isn’t an outlier; it’s a bellwether. In Maine, regulators have begun to crack down on sludge composting operations. In September 2025, Casella announced it was shutting down its Hawk Ridge facility in Unity Township because stricter rules made business “unsustainable” (The Maine Monitor).

What happened in southern New Hampshire exemplifies how deeply flawed the narrative of “toxic compost as green recycling” really is.

Why It Matters

EPA’s own draft risk assessments acknowledge that while biosolids are applied to a fraction of US farmland, reducing PFAS in sludge could significantly lower human and ecological exposures. Yet regulation lags far behind the science.

If Merrimack’s experience teaches us anything, it’s this: without modernized standards that address chemical contaminants like PFAS, sewage sludge composting is not a climate solution—it’s greenwashing.

The public deserves transparency, and our soils and water deserve protection. Until then, “sustainable compost” may carry risks we can no longer afford to ignore.

Mindi Messmer, MS, PG, CG is an environmental and public health scientist and author of Female Disruptors: Stories of Mighty Female Scientists. The book is available on Amazon, Barnes & Noble and through your local bookstore.

Woah. Totally makes sense that bioamplification would be a problem with PFAS in composed sewage, but I never thought about it before. Thanks for the information